Systemic Explorer / Speculative Envisioner / Strategic Planner

Scroll up to see my previous work

Soft robotics & Inflatables

Exploring posthuman thinking through designing a multisensory VR installation redefining the human body

Designing interactive interventions / Qualitative research / Constructive design research methods

Design Research Project - 2021

Theory-informed UX design / Prototype-driven research / Human-centered interaction systems

Design Project - 2021

Interactive Speculative Design

Designing a speculative product to debate the future of powdered food preparation and consumption

2021

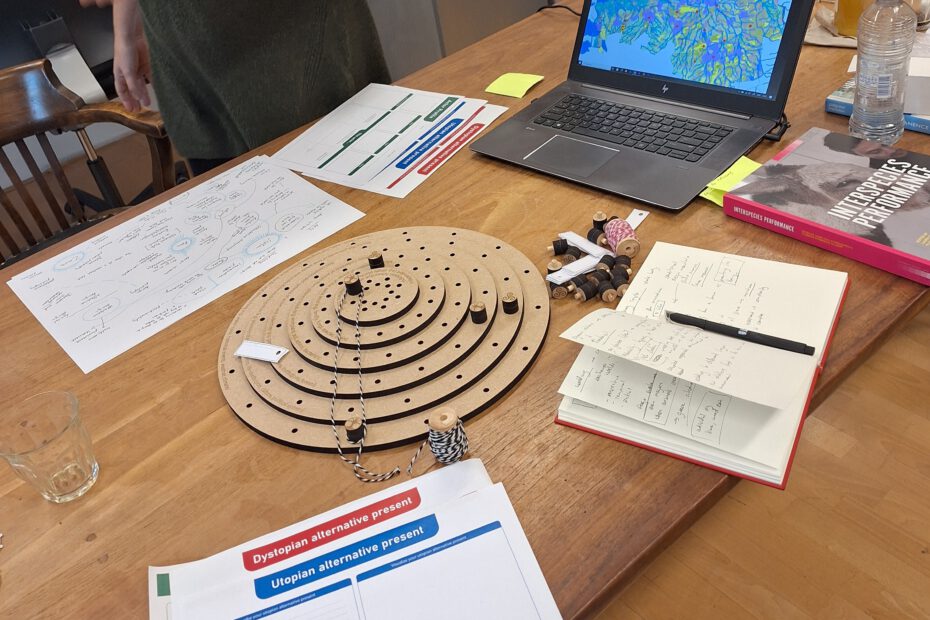

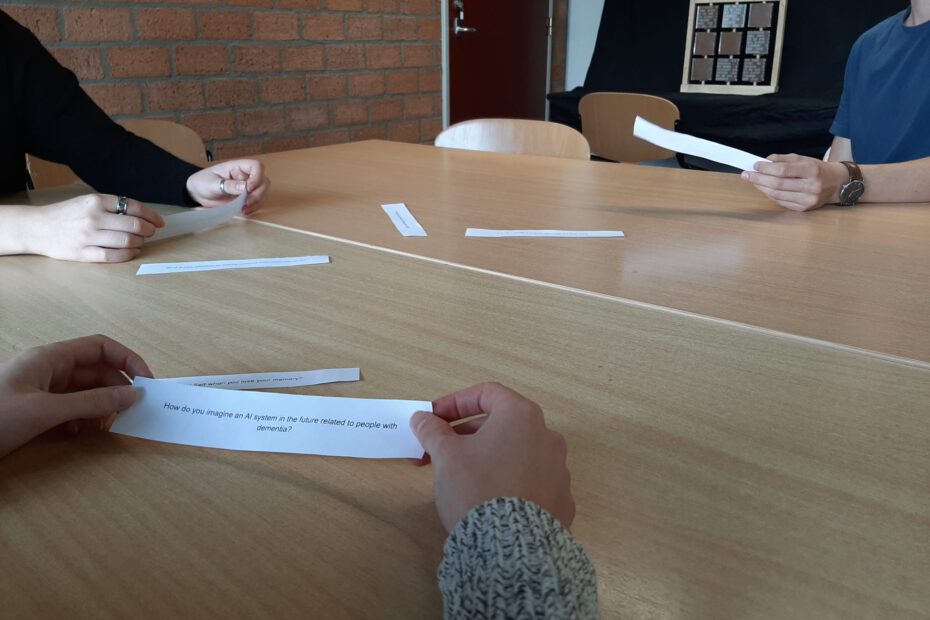

Co-speculation & Futuring

Breaking the cycle of needs through manipulation cards in a participatory futuring study

2022

Philosophy of Technology and Innovation

Developing a critical and ethical design approach through philosophical exploration of technology

2022

Hands-on material experimentation / Sensory design & emotional engagement / User perception analysis

Design Research Project - 2023

"Minor key" & More than Human Design

Exploring the minor key in both the design process and design within a more-than-human context

2023

Immersive Light Design

Shaping narrative through light by concepting and prototyping interactive installations for public events

2023

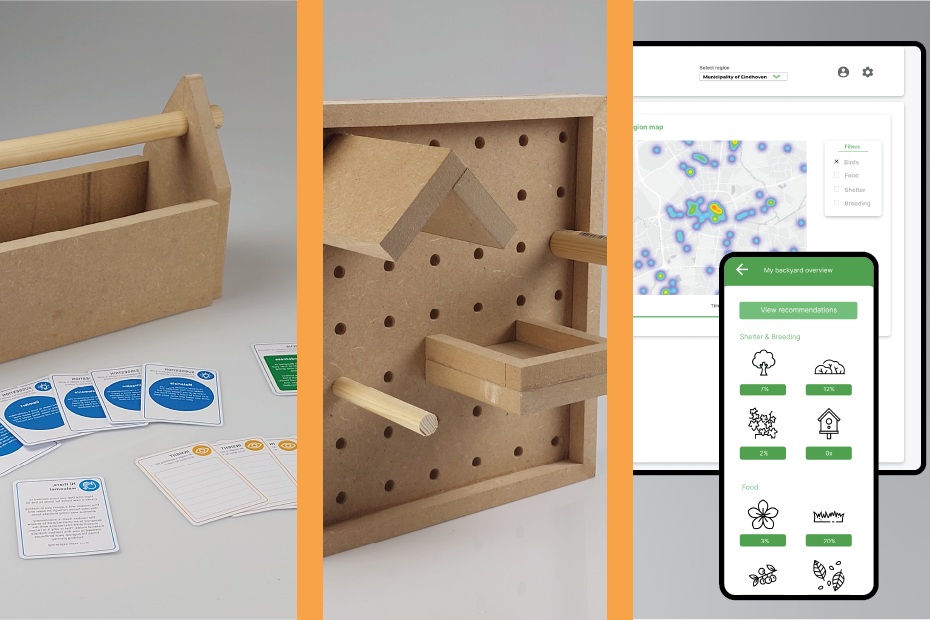

User Experience & Mātauranga Design

Improving the human-nature relationship in urban areas & including Māori worldviews in design

2023

Socio-ecological Design & Innovation

Exploring the worlds of socio-ecological innovation navigated by design philosophy correspondence

2025

Creating meaningful experiences built on complex theory

/About me

I am a design researcher driven to find new ways of dealing with complex societal issues through a transdisciplinary attitude, bringing together systemic exploration, speculative envisioning, and strategic planning to support the creation of more socially and ecologically sustainable worlds.

/ My view on design

Design can act as a facilitator that pollinates multidisciplinary expertise, enabling new situated knowledge(s) to emerge. In this role, design becomes a space for shared thinking, shared sensing and shared decision-making. Supporting designers, users and stakeholders to take meaningful steps toward more just and socio-ecologically sustainable worlds.